Kangaroo Mother Care & Skin to Skin Care: What You Need to Know

Table of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- What Is Kangaroo Mother Care?

- Why Was Kangaroo Mother Care Developed?

- What Is the Evidence for Kangaroo Mother Care?

- What Is Skin-to-Skin Care?

- Kangaroo Mother Care

- Skin-to-Skin Care

- Physiological Benefits of SSC

- Thermal Synchrony

- Skin-to-Skin Care and Mother-Baby Attachment Behaviors

- The Sacred Hour

- Brain Benefits of Skin-to-Skin Care

- Skin-to-Skin Care After a Cesarean Section

- Barriers to Skin to Skin Contact After a C/Section

- Skin to Skin During a C/Section

- Why Did Moms and Babies Come to Be Separated in the First Place?

- Risks of Skin-to-Skin Care

- Summery

Key Takeaways

- Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is a newborn-care method originally developed for premature and low-birth-weight (LBW) babies.

- KMC involves placing the baby between the mother’s breasts in direct contact with the skin.

- Studies have found a variety of vital benefits to KMC, including promoting mother-baby bonding, reducing infant mortality rates, and improving newborn breastfeeding.

What Is Kangaroo Mother Care?

Kangaroo mother care (KMC) is a newborn care strategy created by a team of pediatricians at the Maternal and Child Institute in Bogota, Colombia.

In the original version of KMC, the infant is placed in continuous skin-to-skin contact in a vertical position between the mother’s breasts and beneath her clothes. The newborn is exclusively (or nearly exclusively) breastfed.

32 years after its development, KMC is now recognized by global experts as an integral part of essential newborn care. Analysis of trials of continuous KMC in low- or middle-income countries has demonstrated a drop in neonatal (newborn) mortality from 70% to 30%.

Why Was Kangaroo Mother Care Developed?

Newborn deaths currently account for approximately 40% of all deaths of children under 5 years of age in developing countries. More than 20 million babies are born premature and/or with low birth weight (LBW) each year, and 95% of these cases occur in the developing world.

Birth weight is a significant determinant of newborn survival. LBW (less than 3.3 pounds) is an underlying factor in 60–80% of all neonatal deaths. Prematurity is the largest direct cause of neonatal mortality, accounting for an estimated 29% of the 3.6 million neonatal deaths every year.

LBW and premature babies are at greater risk of illness and death because they lack the ability to control their body temperature (i.e., they get cold, or hypothermic, very quickly). When cold, newborns stop feeding, and are more susceptible to infection.

High neonatal mortality and infection rates can also be attributed to overcrowded nurseries, inadequate staffing, and a lack of equipment. In most countries, the use of incubators is standard for maintaining the body temperature of LBW babies, but they are not widely available in developing countries. And when incubators are available, problems such as poor maintenance, power outages, and lack of replacement parts reduce the number of available, functional incubators.

KMC was developed as an alternative method to caring for preterm and low-birth-weight infants in countries with limited resources and a lack of quality incubators. It was aimed at helping infants who had overcome initial postpartum problems to eat and grow.

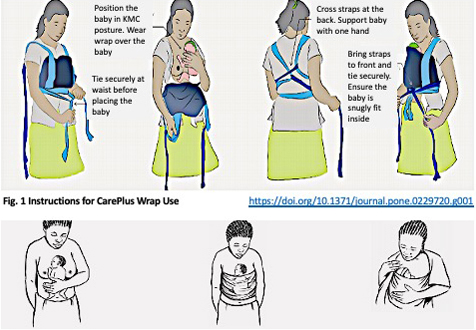

Securely wrap the baby in KMC position and put on loose clothing over the wrap (source: Microsoft Word – MCHIP KMC Guide)

What Is the Evidence for Kangaroo Mother Care?

More than 300 hospital-based studies have compared incubator care with KMC in both developing and developed countries. For stable newborns, most studies demonstrated that KMC offers certain benefits over incubator care.

Benefits of Kangaroo Mother Care

- Maintaining adequate body temperature.

- Reducing hospital-acquired infections or infections passed to you from the hospital environment.

- Increasing exclusive breastfeeding.

- Improving the baby’s weight gain.

- Fostering greater maternal and family involvement in the infant’s care.

All of this was accomplished at a lower cost than incubator care. As a result of these studies, the practice of KMC was introduced in more than 25 countries by 2004.

In 2003, additional studies looked at KMC for low birth weight infants. They found that compared with babies cared for in incubators, KMC reduced:

- Severe illness.

- Infection.

- Breastfeeding problems.

- Maternal dissatisfaction with the method of care.

They also found that KMC improved mother-baby bonding and weight gain after the first week of life.

In 2011, 35 studies involving KMC were analyzed. This review demonstrated even more positive results. Compared with conventional neonatal care, KMC was found to reduce:

- Mortality after discharge.

- Severe infection/sepsis

- Hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections.

- Hypothermia (low body temperature).

- Severe illness.

- Lower respiratory tract disease.

- Length of hospital stay.

The 2011 review also revealed that KMC resulted in improved:

- Infant weight and length.

- Infant head circumference.

- Breastfeeding.

- Mother-infant bonding.

- Maternal satisfaction with the method of care.

Psychological Benefits of KMC

Many studies have also looked at the effect of KMC on infant development and parent-child interactions.

A study published in 2002 compared preterm infants who received KMC to similar preterm infants who received traditional incubator care. They found that compared to traditional care, KMC had many positive maternal effects.

Maternal Psychological Benefit of KMC

- Better positivity and adaptation to infant cues.

- More touching, kissing, and looking into the baby’s eyes.

- Holding the baby more and using more positive speaking behaviors with them.

- Less depression and a more positive perception of problems associated with prematurity.

- Providing a better home environment and keeping more follow-up appointments with healthcare providers.

- Breastfeeding longer.

Infant Behavioral Benefits of KMC

- Calmer temperament.

- Were more alert.

- Demonstrated more interaction with parents.

- Scored higher on tests for cognitive development and motor development.

- More organized communication between the nervous system and bodily functions.

Do the Benefits of KMC Extend into Adulthood?

An interesting study from 2017 looked at the adults who had been enrolled in early KMS studies as preterm babies between 1993 and 1996. Researchers wanted to see if the early benefits of KMC persisted into young adulthood.

The researchers used brain imaging, as well as neurophysiological and behavioral tests, to evaluate the participants’ health status and neurologic, cognitive, and social functioning. Results indicated that KMC had significant, long-lasting social and behavioral protective effects even 20 years after the original KMC intervention.

Kangaroo Mother Care has proven benefits for both mother and baby. These benefits are both physical and psychological, short-term and long-term.

What Is Skin-to-Skin Care?

Generally, KMC should not be confused with routine skin-to-skin care (SSC). Instead, SSC is just one aspect of KMC.

Kangaroo mother care involves the early, prolonged, and continuous skin-to-skin contact between the mother and her baby—both in hospital and after early discharge. KMC is a broad package of care that includes support programs for feeding (ideally exclusive breastfeeding) and the prevention and management of infections and breathing difficulties. KMC was originally developed to care for low birth weight (LBW) and preterm infants in impoverished countries.

The three main components of KMC are continuous SSC, exclusive breastfeeding, and early discharge from the hospital (to avoid infection).

Kangaroo Mother Care

The key aspects of KMC are that it:

- Ensures warmth by keeping the baby continuously skin-to-skin with the mother (or a substitute, such as the father) in between feedings.

- Ensures nutrition by supporting the mother to breastfeed her baby exclusively and frequently.

- Provides infection prevention while in the facility. This is also emphasized before discharge when mothers and families are given instruction on hygiene, identifying signs of infection, and the importance of seeking care early.

- Enables early discharge with a follow-up. Mother and newborn can be discharged early, once the baby is able to suckle and is growing well.

- Provides for regular follow-up.

Skin-to-Skin Care

Skin-to-skin care involves placing the naked (or diapered) newborn on the mother’s bare chest (mother’s chest to baby’s chest) and covering the infant with warm blankets to keep him or her dry and warm.

As opposed to KMC, SSC refers to intermittent skin-to-skin contact between the mother and her baby, usually in resource-rich countries. It is used for varying, shorter periods of time and can be performed by both parents.

Intermittent SSC in resource-rich countries has not been associated with decreased mortality but is widely offered to parents for other perceived benefits. It is recommended for all stable babies immediately after delivery as part of routine care to ensure that they stay warm in the first two hours of life. It is also a preferred method when transferring sick newborns to another health facility.

Ideally, skin-to-skin care starts immediately at birth or shortly thereafter, with the baby remaining on the mother’s chest until at least the end of the first breastfeeding session.

There are 3 main types of skin-to-skin care for full-term infants:

- Birth or immediate skin-to-skin care starts during the first minute after birth.

- Very early skin-to-skin care begins 30–40 minutes post-birth.

- Early skin-to-skin care is any skin-to-skin time that takes place during the first 24 hours after delivery.

Physiological Benefits of SSC

There are many well-documented benefits of skin-to-skin contact between a newborn infant and its mother. Skin-to-skin contact improves physiologic stability for both mother and baby in the vulnerable period immediately after birth.

Having SSC with their mother stabilizes the newborn’s:

- Respiration and oxygenation.

- Heart rate.

- Glucose levels (blood sugar).

- Body temperature.

- Blood pressure.

- Stress hormones.

- Gastrointestinal (GI) function.

SSC also decreases crying, increases the quiet alert state, and promotes restful sleep patterns.

Thermal Synchrony

Thermal synchrony is a physiologic response in which the mother’s chest temperature increases to warm a cool baby and decreases to cool an overly-warm baby. This is especially important because a newborn infant becomes wet and easily chilled as he or she leaves the warmth of his mother’s uterus and enters the cool delivery room.

Babies held with SSC right at birth have been found to have higher body temperatures and blood sugar levels compared to those of babies placed in warmers. This was true whether the mother or her partner was holding the baby skin-to-skin.

Skin-to-Skin Care and Mother-Baby Attachment Behaviors

Bonding between mother and baby is crucial for the newborn’s survival.

Benefits of Skin-to-Skin Care

- Increase maternal attachment behaviors.

- Protect against the negative effects of maternal-infant separation.

- Support optimal infant brain development.

- Promote initiation of the first breastfeeding.

- Increase the number of mothers who breastfeed.

- Increase the duration of breastfeeding.

The Sacred Hour

One 2009 study evaluated the possible long-term effects of practices relating to mother-infant closeness versus separation. It was found that SSC and early breastfeeding for 25 to 120 minutes immediately at birth positively affected the mother-infant interaction—even up to one year later. Waiting 2 hours before handing mom the swaddled baby to hold, however, was found to decrease the mother’s responsiveness to her baby, as well as her ability to positively interact with him or her at 1 year.

A similar study found that SSC during the first 25 to 120 minutes made infants less easily frustrated, better able to calm themselves (self-regulation), and better able to interact with their mother at age 1. Babies not experiencing SSC during those first 2 hours were more irritable, less self-regulated, and less interactive with their mothers at year 1.

It was concluded that these findings made evident a short, early, sensitive period after delivery lasting up to 2 or 3 hours. This crucial window is sometimes referred to as the “Sacred Hour.” It is a time when the new member of the family is greeted for the first time and welcomed by his or her parents.

If desired, you may request your delivery team allow this uninterrupted time with your baby. For a clinically stable baby, most hospitals are happy to accommodate this request.

The Love Hormone

What is responsible for these attachment behaviors between mom and baby? Maternal bonding is so necessary for the survival of the newborn that mother nature has not left it to chance.

Oxytocin(brand name Pitocin) is a hormone produced in the brain that has been particularly well-studied in relation to mother-baby attachment. You may hear the oxytocin hormone referred to as the Bonding Hormone, the Love Hormone, or even the Cuddle Hormone. Oxytocin is increased during skin-to-skin contact, and its levels spike whenever the newborn’s hand massages the mother’s breasts.

Effects of the Love Hormone (Oxytocin/Pitocin)

- Prime the mother’s brain to increase her maternal caregiving behaviors.

- Increase relaxation of mother and baby.

- Increase attraction between mother and infant.

- Improve facial recognition.

Multiple studies from the 1970s to 1980s compared behaviors of mothers who had SSC with their newborns to those whose babies were kept in nurseries separate from their mothers except for feedings. The mothers who had even brief early skin-to-skin contact with their infants were more confident and comfortable handling and caring for their babies than mothers who had been separated from their babies. At 3 months, mothers with early skin-to-skin contact kissed their babies more and spent more time looking into their infant’s faces.

Results lasted well beyond the neonatal period. At 1 year, they continued to demonstrate more:

- Touching

- Holding

- Positive speaking behaviors

- Retention of follow-up appointments with their providers

- Continued breastfeeding for twice as long

Additionally, when comparing the crying behavior of babies separated from their mothers to those who experienced skin-to-skin. It has been found that separated infants have ten times the number of cries and forty times the duration of crying.

Brain Benefits of Skin-to-Skin Care

The brain of a newborn infant is immature—it’s only one-quarter of the size it will be in adulthood. While all of the brain’s cells are present at birth, the brain’s development is not yet complete.

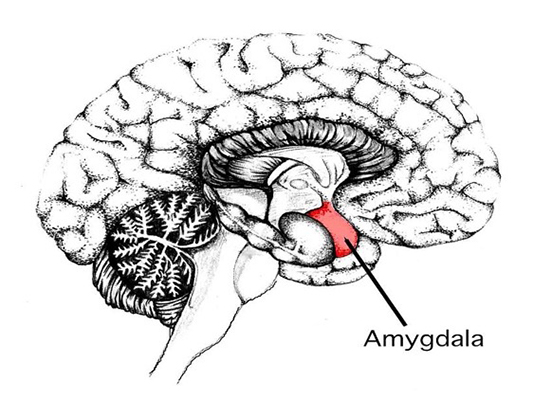

Neurobiologists have been exploring the role of attachment and brain development for many years. They have found that the amygdala, located deep in the center of the brain, is in a critical period of maturation in the first 2 months of life.

The amygdala is part of the system involved in emotional learning and memory. Skin-to-skin contact activates the amygdala and contributes to the maturation of this vital brain structure.

Several studies have shown that the size of the amygdala is larger in babies who experience SSC compared with those who do not.

Several studies have shown that the size of the amygdala is larger in babies who experience SSC compared with those who do not.

Attachment scientist John Bowlby believes that body contact and infant carrying are essential for normal infant development. Being skin-to-skin during the first hour after birth sets a pattern of behaviors between mothers and infants that supports continued body contact and carrying, and thus normal brain development of the infant.

These early experiences may shape brain structure and function. A supportive environment would allow for a brain designed to grow and thrive, whereas a traumatic or hostile environment would cause a brain designed for caution and defensiveness.

Another positive benefit of SSC is that it increases both the rates of and duration of breastfeeding. Compared to the mothers who received routine hospital care, mothers who had skin-to-skin care with their babies:

- Were 24% more likely to still be breastfeeding at one to four months after giving birth.

- Tended to breastfeed their infants an average of 64 days longer.

- Were 50% more likely to exclusively breastfeed between 6 weeks and 6 months.

- Were 32% more likely to breastfeed successfully during their first feed.

The Nine Instinctive Stages

The nine instinctive stages refer to the baby’s sequence of actions when allowed uninterrupted SSC. When skin-to-skin, newborns display an impressive series of behaviors at birth that brings them to the mother’s breast without her assistance. Surprisingly, it is the newborn that initiates breastfeeding—not the mother.

As early as the 1970s, Ann-Marie Widstrom, Ph.D., RN, MTD, a Swedish nurse-midwife, began to notice a pattern in the behaviors of babies that were placed skin-to-skin with their mothers immediately after birth and allowed to adjust peacefully with no interruptions.

Behavioral and physiologic observations of infants and mothers have shown them ready to begin interacting in the first few minutes of life. The most striking observation in the first minutes of life is the ability of the newborn, if warm, dry, and left quietly on the mother’s abdomen, to crawl up to the breast and begin to feed.

This occurs in a 9-part sequence:

- The first stage is the “birth cry,” which occurs immediately after birth as the baby’s lungs expand. It usually ends once the baby is placed onto the mother’s chest.

- The second stage is relaxation. It begins when the birth cry stops and usually lasts for 2 to 3 minutes, during which time the baby is very quiet and still.

- Stage 3 is awakening. This begins with small head movements as the infant opens his eyes and shows some mouthing activity.

- During stage 4, activity, the baby has more stable eye-opening, increased mouthing and suckling movements, and often some rooting activity.

- Resting, stage 5, can occur at any time between the other stages. It is a normal stage, and babies will move on when they are ready. No intervention is necessary.

- During stage 6, crawling, the infant then begins to inch forward using his legs to push strongly into the mother’s abdomen while turning his head from side to side.

- Familiarization, stage 7, begins and may last up to 20 minutes. As he comes near the breast, the odor of the nipple guides the newborn.

- After adequate familiarization, the baby opens his mouth widely to begin feeding—this is stage 8, suckling. This usually occurs about an hour after birth.

- The ninth stage is sleeping, usually between 1.5 and 2 hours after birth.

During all of these stages, the baby moves in a purposeful manner but without frustration or hurry. It can be difficult for those observing to relax and leave the baby and the mother alone without assistance or interference. The skin-to-skin contact keeps the baby warm and is calming and reassuring. He hardly cries when compared with babies swaddled and placed in a warmer.

Together, SSC and breastfeeding enhance maternal response by heightening the mutual gaze between a mother and her newborn, as well as increasing maternal touching. During these times, the infant begins to associate his own actions with those of his mother. SSC promotes the mother’s recognition of, and familiarization with, her infant’s emotional cues.

A DVD or Amazon Prime video entitled “The Magical Hour: Holding Your Baby Skin to Skin During the First Hour After Birth” is a great resource for families. It includes interviews with parents whose babies had been placed skin-to-skin immediately after birth. The DVD includes an explanation of the nine instinctive stages of newborn behaviors and video recordings of babies experiencing each stage.

Skin-to-Skin Care After a Cesarean Section

Rates of SSC are lower after a Cesarean section (C/section) compared to after an uncomplicated vaginal birth. In 2009, only 32% of U.S. birth facilities implemented SSC within 2 hours of an uncomplicated cesarean birth. This figure has improved, however, as more hospitals and birthing centers are establishing new programs to educate staff. According to the CDC, in 2015, the rate had increased to 70%. The rates were lowest (56%) in Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee and highest (81%) in New England states.

Keep in mind, however, that the rate of cesarean births in the U.S. remains high at 32%, leaving a significant number of mothers and babies without immediate SSC. Unfortunately, separation of mothers and infants is still very common after a Cesarean. In the U.S, 75% of women who give birth by Cesarean are separated from their babies for at least the first hour. In 2007, that figure was even higher, at 86%. With more than one-third of mothers in the U.S. now having a Cesarean section, a substantial proportion of mothers and babies experience a critical delay in SSC, bonding, and breastfeeding.

Cesarean birth is known to:

- Reduce the initiation of breastfeeding.

- Increase the length of time before first breastfeeding.

- Reduce the incidence of exclusive breastfeeding.

- Delay the onset of lactation, which increases the likelihood of requiring formula supplementation.

Results of studies have demonstrated that SSC counteracts some of these problems. SSC after a C/section provides:

- Higher maternal satisfaction.

- A birthing experience more like that of a vaginal delivery.

- Decreased maternal anxiety regarding the health and welfare of her newborns.

- Decreased maternal perception of pain.

- A 22% increase in breastfeeding at both one and four months after delivery.

- An increase in exclusive breastfeeding.

- Higher overall rates of breastfeeding (81% versus 69%).

- Fewer problems with breastfeeding.

Unfortunately, some mothers may not be able to independently care for their infants immediately after a cesarean-that is OK. Your baby can still benefit from SSC with your partner.

Barriers to Skin to Skin Contact After a C/Section

- Sleep deprivation

- Sedatives

- General anesthesia (given during an emergency Cesarean)

- Surgical complications

- Bleeding

- Maternal anxiety

- Maternal nausea and vomiting

- Instability in mother or baby

Studies have shown that in cases where immediate SSC between mother and infant was not possible, newborns did better when they received skin-to-skin contact with mom’s partner. Babies who experienced SSC with the partner did better than those swaddled and held or left alone in a warmer. Analysis of data on 95 infants showed that those who received skin-to-skin contact with partners had significantly higher heart rates and wakefulness than babies without this contact. Partner SSC in the operating delivery room has the same positive effects as seen with the mother. Infants cried less and stayed calmer than babies who were placed in warmers.

What Happens Differently When SSC Is Performed in the Operating Room During a Cesarean Section?

If mom and baby are stable, you may still experience skin-to-skin care while undergoing your C/section. A few things are done differently. Many studies have demonstrated that with appropriate education and collaboration, SSC after C/sections can be implemented in the operating room.

Skin to Skin During a C/Section

- Your naked baby is placed on your bare chest between your breast. The baby is dried off and covered with warm blankets.

- Your heart monitor stickers are placed on your side to leave a spot open on your chest for the baby.

- Your gown is left open at the front to allow your baby to lay on your bare chest.

- Your blood pressure cuff and IV are placed on your non-dominant arm.

- Your oxygen monitor is placed on your non-dominant hand or even your toe instead of your finger.

- Weight, measurement, and bathing of the newborn may be delayed.

- Eye ointment may be given while experiencing SSC. Vitamin K shot may be safely delayed up to 6 hours after delivery, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

- Apgar scores, newborn assessment, and placing the ID bracelet may be completed with your baby on your chest.

- There must be adequate nursing staff to continuously monitor mom and baby.

Studies on Skin-to-Skin Care and Cesarean Sections

A review of 46 trials involving SSC during or just after Cesarean delivery reported no adverse effects for mom or baby and no difference in the newborn’s Apgar scores, oxygen levels, heart rate, or temperature when compared with babies who had traditional care.

Researchers have also looked at whether immediate SSC during Cesarean sections influences the rate at which newborns are transferred to the neonatal intensive care (NICU) for observation. They found that after receiving SSC, fewer newborns required transfer (1.8% versus 5.6%).

Numerous quality-improvement reports from hospitals have also described implementing immediate SSC during Cesareans. Hospitals that have implemented this new practice report many benefits, including:

Benefits of Skin-to-Skin Care During C/Section

- Increases in overall and exclusive breastfeeding.

- Safer and healthier neonatal transitions.

- Decreased pain responses in newborns undergoing procedures, such as blood drawing.

- Improved maternal-infant bonding.

- Decreased maternal pain perception.

- Decreased maternal anxiety.

- Greater maternal satisfaction.

Why Did Moms and Babies Come to Be Separated in the First Place?

The separation of mothers and newborns is unique to the 20th century. In the past, infant survival depended on continuous mother-newborn contact. The practice of routinely separating mothers and newborns started in the early 1900s, when women began giving birth in hospitals instead of at home.

Additionally, most women received general anesthesia as pain relief for labor during that time, making the moms and babies very groggy after delivery. Because mothers could not care for their babies right away, hospitals created central nurseries to care for newborns, and infants were typically separated from their mothers for 24–48 hours while under this care.

A tradition of separation of the mother and baby at birth still persists in many parts of the world. In standard hospital care, newborn infants are handed off to the nurse and placed in open cribs or under warmers. Their Apgar score is performed, they receive their eye ointment and vitamin K, and their footprints are taken. The baby is finally swaddled and handed over to mom or dad wrapped in a blanket.

Risks of Skin-to-Skin Care

The AAP has addressed several safety concerns when providing SSC in their article, Safe Sleep and Skin-to-Skin Care in the Neonatal Period for Healthy Term Newborns.

- A newborn requiring resuscitation should be continuously monitored, and SSC should be postponed until the infant is stabilized.

- Low Apgar scores (less than 7 at 5 minutes) or medical complications from birth may prevent immediate SSC.

- Lack of continuous observation of the mother-infant dyad (lapses longer than 10 to 15 minutes) during the first few hours of life is a concern.

- Lack of education and skills among staff supporting the mother-newborn dyad during the transition while skin-to-skin is a concern.

- Unfamiliarity with the potential risks of unsafe positioning during SSC can be problematic.

- Falls may occur during SSC, particularly if the dyad is not continuously monitored.

Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse

The most serious complication from immediate SSC is called sudden unexpected postnatal collapse (SUPC). SUPC is a rare but potentially fatal event in an otherwise healthy-appearing term newborn. Many (but not all) of these events are related to suffocation or entrapment.

SUPC occurs when the infant stops breathing, either temporarily or permanently, followed by cardiorespiratory failure. There are not yet any standard diagnostic criteria because the definition of SUPC varies between physicians studying different patient populations. There is agreement that SUPC occurs in term infants who are well at birth, then unexpectedly collapse within the first 7 days of life and require resuscitation.

Several physicians have suggested standardized procedures for SSC to prevent complications. However, none of the checklists or procedures developed have been proven to reduce the risk. Frequent and repetitive assessments—including observation of newborn breathing, activity, color, tone, and position—may prevent positions that obstruct breathing or lead to events causing sudden collapse. Continuous monitoring by trained staff members and the use of checklists may also improve safety when initiating SSC.

How Can I Safely Position My Newborn During Skin-to-Skin Care?

There are several steps you can take to help ensure your baby’s safety during SSC:

- Be certain that your infant’s face can be fully seen.

- The infant’s head should be in a “sniffing” position.

- The infant’s nose and mouth should remain uncovered.

- The infant’s head must be turned to one side.

- The infant’s neck should be straight, not bent.

- The infant’s shoulders and chest should face their mother.

- The infant’s legs should be flexed (bent).

- The infant’s back (not mouth or nose) must be covered with blankets.

- The mother-infant dyad must be monitored continuously by staff in the delivery room and regularly on the postpartum unit.

- When the mother wants to sleep, the infant should be placed in a bassinet or with another support person who is awake and alert.

If you would like to experience SSC but are too exhausted to do so safely-that is OK. Your baby may bond with your partner while you get well-deserved rest. A rested mom is a happy mom that can pass that positive energy onto her baby.

Summary

Kangaroo mother care and skin-to-skin care immediately after birth are so much more than just nice ways to welcome your newborn into the world. The first 1 or 2 hours after birth are “sacred hours”—a sensitive period crucial for infant brain development, physiologic stability, and optimal psychological and emotional well-being. During this time, long-lasting bonds are formed that carry forward into the future.

SSC and KMC are not only safer for both babies and mothers—they are also endorsed by multiple organizations responsible for the care and well-being of infants. They provide multiple short- and long-term beneficial effects, such as increased breastfeeding, increased maternal attachment behaviors, decreased premature and LBW infant mortality, and protection from the detrimental effects of maternal-infant separation.

As more evidence accumulates, there is little controversy about the benefits of KMC and SSC. Evidence shows that it is possible—and best practice—for mothers and babies to stay together after a cesarean, as well as after a vaginal delivery. Hospitals and birthing centers are beginning to implement the steps necessary to make it a standard of care so that all babies and mothers can benefit from this important and special time.

Written by: Lisa Shephard, MD | Editor: Victoria Menard and Dayna Smith MD | Reviewed April 28, 2022 | Copyright myObMD. Media, LLC, 2022

References

- World Health Organization. (2003, January 1). Kangaroo mother care: A practical guide. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9241590351

- Stubblefield, H. (2017, June 7). What Are Nosocomial Infections? Healthline. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/hospital-acquired-nosocomial-infections

- Types of healthcare-associated Infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, March 26). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/infectiontypes.html

- Nall, R. (2018, February 9). Apgar Score: What You Should Know. Healthline. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/apgar-score

- Phillips, R. (2013). The Sacred Hour: Uninterrupted Skin-to-Skin Contact Immediately After Birth. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 13(2), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2013.04.001

- The Sacred Hour. CHI Health. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.chihealth.com/en/services/maternity/labor-and-delivery/sacred-hour.html

- Carey, E., Zimlich, R., & Lee, S. W. (2022, February 28). Understanding Increased Intracranial Pressure. Healthline. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/increased-intracranial-pressure

- Ellis, M. E. (2018, September 29). Patent Foramen Ovale. Healthline. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/patent-foramen-ovale

- Breastfeeding. World Health Organization. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, August). CDC’s Work to Support & Promote Breastfeeding in Hospitals, Worksites, & Communities. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/breastfeeding-cdcs-work-508.pdf

- Chertoff, J. (2019, January 2). What Is Rooting Reflex? Healthline. Retrieved from: https://www.healthline.com/health/parenting/rooting-reflex#development

- Brimdyr, K. (n.d.). About the 9 Stages. The Magical Hour. Retrieved from: http://magicalhour.org/aboutus.html

- Brimdyr, K. (n.d.). The Magical Hour: Holding Your Baby Skin to Skin in the First Hour After Birth. Amazon.com. Retrieved from: https://www.amazon.com/Magical-Hour-Holding-First-Brimdyr/dp/B01EGQRDSU

- Feldman-Winter, L., & Goldsmith, J. P. (2016). Safe Sleep and Skin-to-Skin Care in the Neonatal Period for Healthy Term Newborns. Pediatrics, 138(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1889

- Tsang, L. P., Ng, D. C. C., Chan, Y. H., & Chen, H. Y. (2019). Caring for the mother-child dyad as a family physician. Singapore Medical Journal, 60(10), 497–501. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2019128

- Herlenius, E., & Kuhn, P. (2013). Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse of Newborn Infants: A Review of Cases, Definitions, Risks, and Preventive Measures. Translational Stroke Research, 4(2), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12975-013-0255-4

- Ayala, A., Christensson, K., et al. (2021). Newborn infants who received skin‐to‐skin contact with fathers after caesarean sections showed stable physiological patterns. Acta Paediatrica, 110(5), 1461–1467. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.15685

- Bera, A., Ghosh, J., Singh, A.K., et al. (2014). Effect of kangaroo mother care on growth and development of low birthweight babies up to 12 months of age: a controlled clinical trial. Acta Paediatrica, 103(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12618

- Bergman, N.J., Linley, L.L., Fawcus, S.R. (2004). Randomized controlled trial of skin‐to‐skin contact from birth versus conventional incubator for physiological stabilization in 1200‐ to 2199‐gram newborns. Acta Paediatrica, 93(6), 779–785. doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb03018.x

- Boyd, M.M. Implementing skin-to-skin contact for Cesarean birth. (2017). AORN Journal, 105(6), 579–592. 10.1016/j.aorn.2017.04.003

- Cattaneo, A., Davanzo, R., Worku, B., et al. (1998). Kangaroo-mother-care for low birthweight infants: a randomized controlled trial in different settings. Acta Paediatrica, 87(9). https://doi.org/10.1080/080352598750031653

- Chavula, K., Guenther, T., Valsangkar, B., et al. (2020). Improving skin-to-skin practice for babies in kangaroo mother care in Malawi through the use of a customized baby wrap: A randomized control trial. PLoS One, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229720

- Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care (mPINC™) Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, January 27). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/mpinc/index.htm?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fbreastfeeding%2Fdata%2Fmpinc%2Fresults-tables.htm

- Christensson, K., Cabrera, T., Christensson, E., et al. (1995). Separation distress call in the human neonate in the absence of maternal body contact. Acta Paediatrica, 84(5), 468–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13676.x

- Davanzo, R., De Cunto, A., et al. (2014). Making the First Days of Life Safer: Preventing Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse while Promoting Breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334414554927

- Elliott-Carter, N., & Harper, J. (2012). Keeping Mothers And Newborns Together After Cesarean: How One Hospital Made the Change. Nursing for Women’s Health, 16(4), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-486x.2012.01747.x

- Erlandsson, K., Dsilna, A., Fagerberg, I., & Christensson, K. (2007). Skin-to-skin care with the father after cesarean birth and its effect on newborn crying and prefeeding behavior. Birth, 34(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-536x.2007.00162.x

- Feldman-Winter, L., & Goldsmith, J. P. (2016). Safe Sleep and Skin-to-Skin Care in the Neonatal Period for Healthy Term Newborns. Pediatrics, 138(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1889

- Baley, J., & Watterberg, K., et al. (2015). Skin-to-Skin Care for Term and Preterm Infants in the Neonatal ICU. Pediatrics, 136(3), 596–599. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2335

- Ferrarello, D., & Carmichael, T. (2016). Sudden Unexpected Postnatal Collapse of the Newborn. Nursing for Women’s Health, 20(3), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2016.03.005

- Gabriel, M.A., Martin, L., Escobar, A.L., et al. (2009). Randomized controlled trial of early skin-to-skin contact: effects on the mother and the newborn. Acta Paediatrica, 99(11), 1630–1634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01597.x

- Graven, S.N. (2004). Early neurosensory visual development of the fetus and newborn. Clinics in Perinatology, 31(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2004.04.010

- United States Agency of International Development. Kangaroo Mother Care Implementation Guide. Maternal and Child Health Integrated program. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.mchip.net/sites/default/files/MCHIP%20KMC%20Guide_English.pdf

- Laudert, S., Liu, W., Blackington, S., et al. (2007). Implementing potentially better practices to support the neurodevelopment of infants in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology, 27, S75–S93. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211843

- Mahlmeister, L.R. (2005). Couplet Care After Cesarean Delivery: Creating a Safe Environment for Mother and Baby. The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing, 19(3), 212–214. Retrieved from: http://journals.lww.com/jpnnjournal/Citation/2005/07000/Couplet_Care_After_Cesarean_Delivery__Creating_a.5.aspx

- Matthiesen, A., Ransjö-Arvidson, A., Nissen, E., Uvnäs-Moberg, K. (2001). Postpartum maternal oxytocin release by newborns: effects of infant hand massage and sucking. Birth, 28(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536x.2001.00013.x

- McGrath, S.K., Kennell, J.H. (2007). Extended mother-infant skin-to-skin contact and prospect of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatrica, 91(12). 1288–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb02819.x

- Moore, E. R., Bergman, N., Anderson, G. C., & Medley, N. (2016, November 25). Early skin‐to‐skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Retrieved from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/table-of-contents?volume=2017&issue=12

- Pejovic, N.J., Herlenius, E. (2013). Unexpected collapse of healthy newborn infants: risk factors, supervision and hypothermia treatment. Acta Paediatrica, 102(7), 680–688. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fapa.12244

- Phillips, R. (2013). The Sacred Hour: Uninterrupted Skin-to-Skin Contact Immediately After Birth. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews, 13(2), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.nainr.2013.04.001

- World Health Organization. Maternal and Newborn Health/Safe Motherhood. (1997). Thermal protection of the newborn: a practical guide. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63986

- World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research. (2003). Kangaroo mother care: a practical guide. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42587/9241590351.pdf?sequence=1